Have you ever played Catan? Maybe even Age of Empires or Starcraft II?

I’ve played enough video games myself to know that the player with the most resources almost always wins. Without resources, you can’t build your economy. You can’t build up your defences. Your opponents will pull ahead. And resources are scarce. A recipe for fierce competition.

Europe has plenty of wood, grain, and stone. But the competition of today and the future is all about critical raw materials. These metals and minerals are called “critical” because they’re irreplaceable for producing all modern technology. From solar panels and electric cars to the microchips that power every high-tech gadget.

What oil was for the 20th century, these critical materials are for the 21st. Without them, our modern economy and society will grind to a halt. And they’re essential building blocks for the future. But now that Europe needs them more than ever, we’re dependent on other countries, especially China.

The danger of this dependence is becoming clearer by the day. After China restricted exports of certain rare earths in April, some European producers had to shut down production. The stakes for Europe’s economy and future couldn’t be higher. Can Europe manage to secure these vital resources?

No future for Europe without resources

For all its major challenges, Europe depends on critical materials. They’re crucial for clean technology and Europe’s green transition, the digital transition (think microchips, data centers, and AI) and the defence industry. In critical sectors like energy and infrastructure, Europe already wants to become less dependent on other countries, especially China and the U.S.

But competition for these resources is fierce, and global demand is exploding. The International Energy Agency expects demand to triple by 2030. For some minerals demand will grow even faster. The EU predicts that by 2030, demand for rare earths within the EU will increase sixfold, and demand for lithium will be twelve times higher.

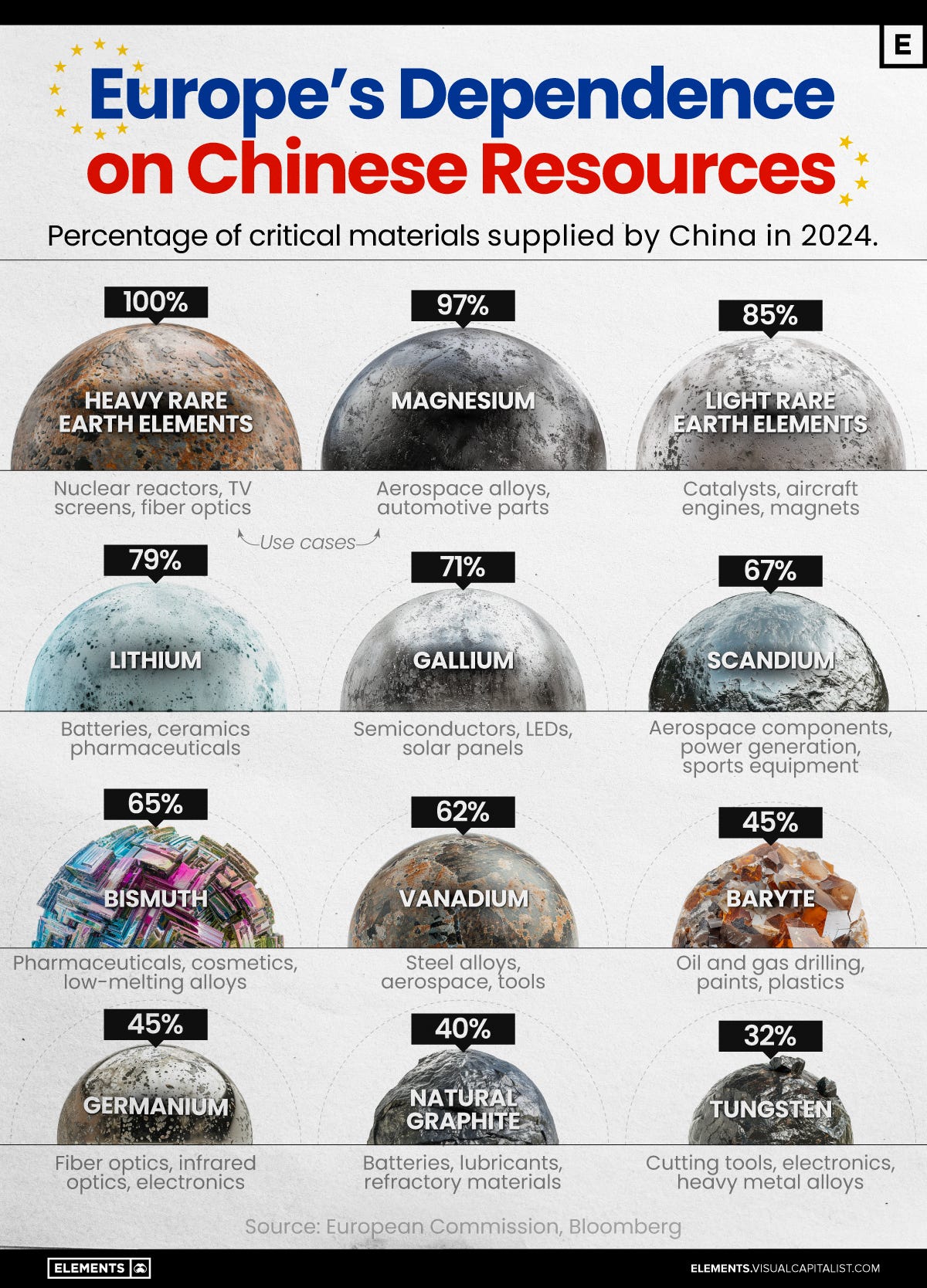

Another reason these resources are deemed “critical” are the hugh risks if supplies were to stop. For many of these materials, the world depends on three countries, or sometimes just one single supplier. The EU gets 100% of its heavy rare earths from China, 97% of its lithium and magnesium imports from China, 99% of its boron from Turkey, and 71% of its platinum from South Africa.

In China’s grip - again

Europe depends the most on China by far. If you’re thinking, “here he goes again with his China obsession,” I mention China so often because China it’s involved in every big challenge Europe faces. And it’s playing the game much more strategically than we are. Over the past decades, China has built an unmatched supply chain through massive investments, while supply chains in countries like the US have faded away.

There are enough critical resources underneath the ground worldwide, but there aren’t enough in circulation. First, they have to be mined. Next, they’re separated to extract the desired materials (refining). Then, those refined materials are processed into usable forms. Finally, semi-finished products go into technologies like batteries, wind turbines, or smartphones.

China plays a leading role in every stage of this process, making it indispensable to other countries. It refines 99% of Congo’s cobalt and 94% of Australia’s lithium. In 2023, China accounted for roughly 60% of global production of critical resources, and even 85% of the processing.

And thanks to state subsidies and dumping on international markets, China holds quasi-monopolies on many end products. In 2023, 98% of Europe’s solar panel imports came from China, as did 87% of imported electric vehicle batteries.

Dependencies make us vulnerable

This dependence leaves Europe vulnerable to export restrictions or other disruptions. I don’t know, something like a pandemic or trade war. Countries like China can weaponize these dependencies, and they’ve started doing exactly that.

As retaliation for Trump’s tariffs, China restricted exports of rare earth metals and the magnets made from them in April. Now, companies need permits to import them. But with so many applications, many European firms haven’t gotten permits, or their applications have been denied. This has caused shortages because China produces and processes over 90% of the world’s rare earth supply. A European diplomat called it “the biggest example of Chinese economic coercion ever.”

Because of these shortages, the European Chamber of Commerce in China warned that European production of certain goods could grind to a halt within weeks. Just yesterday, Handelsblatt reported problems in German industries like defense. The European Association of Automotive Suppliers even says several suppliers of electric motors had to shut down production. Companies’ stocks of rare earths ran out in less than two months.

In this way, Europe risks trading its dependence on Russian energy for dependence on Chinese minerals. That’s exactly what EU Commissioner Stéphane Séjourné recently warned for: “Chinese lithium will not become the Russian gas of the future.” But that’s exactly what it already is.

And because of this dependence, Europe risks getting caught in a vicious cycle. Industries need resources and energy. If European companies can’t get resources, they’ll be wiped out by competitors in countries that do have them. A strong (defence) industry is needed in turn to keep the military industrial complex going, and military power is needed to protect resources as they’re shipped across the world.

Resources → Economy → Military → Resources. If you don’t have resources, you lose. Gamers can tell you all about it.

Global race with China and the US

China is way ahead in this global race. It’s not just mining and processing a lot of resources at home. It’s also secured exclusive access to mines abroad. China has invested at least €50 billion in mining and refining projects worldwide.

Like on the African continent, which holds a third of the world’s reserves of critical materials. The Democratic Republic of Congo produces 70-80% of the world’s cobalt, and China owns 72% of Congo’s cobalt and copper mines. Thanks to infrastructure investments worth billions under China’s Belt and Road Initiative, those resources are then shipped to China for processing.

The United States is stepping in more and more as well. To counter Chinese influence, it’s negotiating with Congo for mineral access in exchange for multi-billion-dollar investments. And the US is meddling in Europe as well. He talked about “buying” Greenland and didn’t exclude military intervention. Greenland has some of the world’s biggest reserves of rare earths and other materials. And in May, the US signed a mineral deal with Ukraine, promising joint investments in return for a share of future profits and preferential access. In 2023, Forbes estimated that Ukraine’s resources could be worth nearly $15 trillion.

The EU has legislation

Europe is getting in on the action, too. Following COVID, Russia’s war in Ukraine, Trump, and other sorts of geopolitical violence, the EU is realising more and more that it needs to be less dependent and more self-sufficient, especially in strategic sectors.

To reduce dependencies and mine and process more minerals at home, the EU’s “Critical Raw Materials Act” went into effect last year. It identified 34 materials as critical.

But the EU has plenty of strategies and fancy words. Look at any European law, like the Chips Act or the Net-Zero Industry Act, and you’ll see goals, targets, and promises that often don’t end up being met.

The Critical Raw Materials Regulation also has goals and targets. By 2030 it aims for:

10% of annual resource demand to be sourced within the EU;

40% of annual demand to be processed within the EU;

15% of annual demand to be recovered through recycling in the EU;

Dependence on any single non-EU country to be no more than 65% of annual consumption for each material.

To hit these targets, the EU wants to open more mines in Europe and process more materials. In March, it announced 47 strategic projects in 13 member states. More lithium should be mined in Portugal and Spain for example. Portugal’s lithium could even cover almost all EU demand through 2050. The European Investment Bank also announced €2 billion in investments for critical materials projects in March.

But these investments are coming too late. It takes ten to fifteen years on average, to get a new mine up and running, while global demand will have more than tripled by then. Right now, there’s just one operating lithium mine in Europe. And new mines spark protests across Europe because of pollution concerns. Plans for mines in Portugal and Serbia have been halted. It’s a matter of “not in my backyard”: people recognise the importance of mines but don’t want one in their own backyard.

When it comes to recycling, Europe can still improve. Every electric vehicle, solar panel, or drone made or imported into Europe contains resources that can be reused. Up to 95% of cobalt and nickel can be recovered. Estimates suggest the EU could meet 40–75% of its demand for certain metals through recycling. Yet today, Europe recycles almost no lithium or rare earths.

EU must step up game abroad

But Europe will mainly have to step up its game outside of the EU. Some resources simply don’t exist here, and opening new mines takes too long. In recent years, the EU has signed 13 “strategic partnerships” with non-EU countries. The EU promises investments in things like infrastructure. But with all these “dialogues,” “roadmaps,” and “frameworks,” it’s still vague what Europe will concretely get in return.

Yesterday, the European Commission presented 13 strategic non-EU projects that are more concrete. The EU will work with the UK to mine tungsten and with Ukraine for graphite.

Still, Europe is missing plenty of chances. Although it signed a deal with Ukraine in 2021, the US deal with Ukraine is bigger and gives American companies priority. Meanwhile, Ukraine has 25 of the 34 critical resources the EU listed as critical, plus the world’s largest titanium reserves and 20% of global graphite.

Greenland is similar. The EU is investing in a project there and opened a special office last year. But last month, Greenlands Minister urged European investors to hurry up, warning it could turn to China.

Outside Europe, the EU is hindered by its own rules and standards. European investors are less competitive for African mines because strict sustainability rules slow down permits and approvals. For African countries, jobs, infrastructure, and industrial growth are bigger priorities. China and the Gulf states ask fewer conditions, making them more attractive investors. Europe is “too clean to compete.”

This creates a Catch-22. The EU needs materials for its green transition, but its own sustainability standards hamper its ability to secure them. As a result, Europe will become even more dependent on other countries for the resources and the technologies that need them.

If Europe really wants to reduce that dependency, it should act in a more realist way. Through its Global Gateway initiative, the EU can invest up to €300 billion in infrastructure outside Europe. If Europe wants to compete in this global race, it shouldn’t start from behind.

Back to Catan, or any other strategy game: it’s hard to win if you restrict yourself more than opponents. If you want to build, you need resources. If you don’t have them, you’ll lose. I can still hear that voice in Starcraft II saying: “Not enough minerals.”