Why the EU doesn't speak with one voice on the global stage

Division gives Trump and Xi the upper hand

With only five days left, the EU must clinch a trade deal with the US to avoid 50% American tariffs on all European exports. In a last-ditch effort, Trade Commissioner Šefčovič is back in Washington today, negotiating with his American counterpart. After all, the European Commission signs trade agreements on behalf of all 27 member states.

Yet US Commerce Secretary Lutnick has eagerly picked up from the media that the European camp is divided. European leaders such as German Chancellor Merz, Italian Prime Minister Meloni, French President Macron and Dutch Prime Minister Dick Schoof cranked up the pressure in Brussels last week, insisting that a modest deal is better than none at all. Major industrial nations are already feeling the pain of US tariffs like 25% on steel, aluminum, and cars, and fear Trump’s threatened 50% hike.

Merz called for a “swift framework agreement,” arguing that German sectors like chemicals, steel, and pharma are suffering too much from the American tariffs already in place. He blasted the Commission’s negotiating tactics as “far too complicated.” Last month, the US trade chief said that “Germany wants a deal, but isn’t allowed one.” It was no coincidence that Commission President von der Leyen met with 13 German industrial CEOs yesterday, five days before the US deadline.

Italian Prime Minister Meloni meanwhile claimed that a 10% tariff “wouldn’t have that much impact.” Italy, keen to keep good ties with the US, is prepared to accept a lot (i.e., absorb economic hits). Spain, on the other hand, has spent recent months urging the EU to reject even a 10% levy.

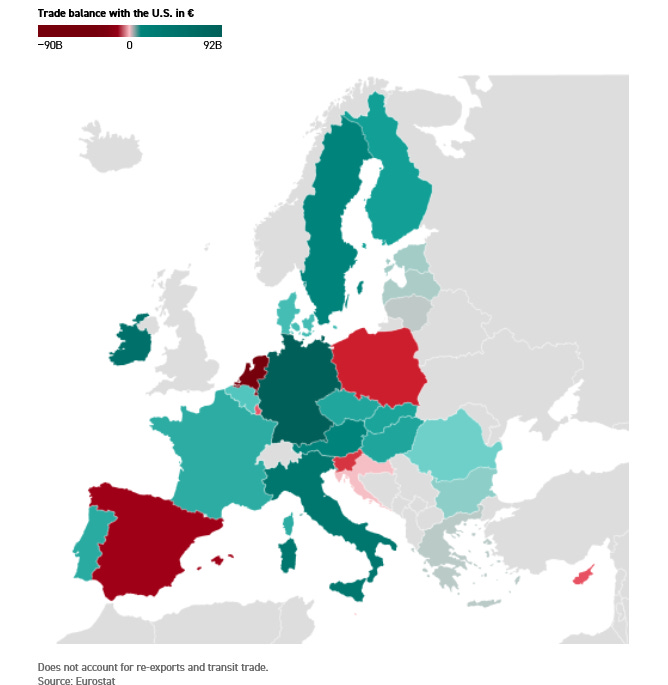

Today, the EU seems ready to accept a 10% tariff on all exports to avert more economic damage. “On paper,” the EU has formidable tools to strike back: its single market is the world’s largest, as is its trade relationship with the US. But internal divisions keep those tools on paper. Europe stands by as Trump slaps tariffs on us, without even daring to lift a finger in return.

The end result: European exports have filled the US Treasury with billions, European companies’ competitiveness is weakened, and the EU has proven that Trump’s threats work. Maybe Trump isn’t as clueless as most Europeans think.

More importantly, the US doesn’t have to satisfy 27 nations in these talks. Those 27 member states each have their own lobby groups, industries and economic priorities, and voters to please. Who needs external rivals with such internal divisions?

Europe’s impotence on Israel-Gaza

EU–US trade talks are just one example of a recurring pattern. Many leaders deliver high-minded speeches in the European Parliament about the power of unity and the need for a stronger Europe on the world stage. But when it really counts and national interests are at stake, that idealism melts away under the French, Italian, or Polish sun.

Because EU foreign policy requires unanimity among all 27 members, the Union can’t speak with one voice on critical issues. Instead, it’s a cacophony in 24 official EU languages. In practice, there is no EU foreign policy. That undermines the EU’s strength and international credibility.

The EU has done far too little in the Gaza war because it’s hopelessly split between more pro-Palestinian countries (Ireland, Spain, France, Belgium, Slovenia) and more pro-Israeli ones (Germany, Italy, Czechia, Austria), with “moderates” like Greece, Cyprus, Poland and recently the Netherlands in between. Eleven of the 27 member states recognize a Palestinian state; the rest do not.

It took nearly three weeks after the October 7 attack for the EU to issue a joint statement. Leaders first haggled for hours over a single letter ‘s’: “humanitarian pause” versus “pauses.” From personal experience with European Parliament resolutions on Israel–Gaza, I can tell you that individual words are indeed much debated. But Israeli Prime Minister Netanyahu has not been impressed by European statements.

The EU does in fact have leverage. It’s Israel’s largest trading partner (accounting for 32% of its total international trade) and the biggest aid donor to Gaza. Yet the EU stands on the sidelines while the US brokers ceasefire talks. That’s because, in practice, with regards to Israel-Gaza, there is not ‘one EU’.

The High Representative as moderator

There’s even division within EU institutions. One day after October 7, Commission President von der Leyen had the Berlaymont building lit in Israel’s flag colors. A week later, she visited Israel to stress Israel’s right to self‑defense. EU High Representative Josep Borrell, Europe’s foreign minister in theory, was far more critical of Israel.

To add to the complexity, there was also Council President Charles Michel, who in theory speaks for all 27 Member States. In practice, he made little impact and ended up bickering in the media with von der Leyen. Even personal egos stand in the way of one EU foreign policy.

Nearly two years on from October 7, European division over Gaza persists. In June, on behalf of 18 member states, the Commission examined whether Israel was respecting the Association Agreement and whether it violated human rights in Gaza. Under the agreement, a minimum of 15 countries can suspend Israel’s trade privileges with the EU.

But tensions between Israel and Iran delayed any decision, and nine states were already skeptical of the probe. High Representative Kaja Kallas faces an impossible task: she must unify 27 capitals on issues that often have 27 different takes, then represent the whole EU internationally. But she spends most of her time mediating within Europe, not conducting diplomacy abroad. Instead of a true EU foreign minister, the High Representative functions as a moderator, preventing further divisions among member states.

China exploits EU divisions

The EU is similarly divided on China, where competing economic interests drive a wedge between Member States. For years, China has leveraged these national divisions to weaken EU economic countermeasures, like the tariffs of up to 45% on Chinese electric vehicles. But countries that export a lot to China, notably Germany, voted against these levies and demanded carve‑outs for their industries, undermining the EU’s negotiating position and credibility.

China also invests strategically in ports and infrastructure in European countries to deepen ties and mute criticism. A decade ago, many Central and Eastern European countries were far less critical of China when they took part in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, drawing billions in investments. Chinese factories in countries that are eager for investment such as Hungary and Spain, allow China to bypass EU import duties, and to sell goods across the single market.

And instead of sending one EU delegation, we see an endless parade of national leaders to Beijing, almost begging Xi Jinping to relief tariffs. More Belgian pork heads to China, more French cognac is celebrated, and Spain’s Sánchez even called China an “essential partner” in April. In April 2023 Macron even sowed doubt about defending Taiwan just before von der Leyen’s trip to China. National leaders keep undermining the EU’s strategy.

Keep divisions behind closed doors

A solution that is often proposed is to scrap the unanimity rule and switch to qualified majority voting. So that a decision on EU foreign policy could pass with, say, 15 out of 27 votes. Twelve member states back this reform. Indeed, it’s hard to justify that one country, Hungary under Viktor Orbán, can block decisions on Ukraine that 26 others support, endangering Europe’s security. Those 26 often take informal action outside formal channels to break the deadlock.

But the examples above show it’s not just Orbán at fault. And should foreign policy really be decided by majority vote? Sure, it speeds things up. But those in opposition will feel sidelined. A statement backed by 15 countries but opposed by 12 still doesn’t mean the EU speaks with one single voice. And often the issue isn’t a lack of decisions, but a lack of political will in member states to implement them. Finally, the EU isn’t a state. It’s a project of partnership between 27 countries. This means that the EU must listen, negotiate compromises, and balance interests.

For the next six months, Denmark holds the presidency of the Council of the EU, and will strive to align the 27 under the banner “A Strong Europe in a Changing World.” That strong Europe requires managing the internal divisions that are inevitable with 27 members behind closed doors, and the EU to speak with one voice on the international stage. Because for Trump, Xi, and Putin, European division is their greatest Trump card.