Challenges after the NATO summit

How can Europe strengthen defence industry and who will pay the price for 5%?

Praise-filled text messages, meeting the Royal Family which “daddy” Trump is sensitive to, including a sleepover at the royal palace. Maybe President Trump even got ‘hagelslag’ at his breakfast. The result: a happy Trump, every country officially signed up to the 5% defence-spending target, and the US pledged its commitment to NATO in word and writing.

Power and influence are all about getting others to do what you want. In that sense, the NATO summit was a diplomatic masterclass and should be required reading for future international relations students. NATO Secretary-General Rutte even let Trump claim the outcome as his ‘win,’ straight out of How to Win Friends & Influence People.

It’s worth imagining the alternatives and noticing what Trump didn’t do: he didn’t storm off in anger, didn’t threaten to pull the US out of NATO again, and said nothing about refusing to defend other member states.

The people who called Mark Rutte’s performance “embarrassing for Europe” base this on how they think the world should be. But international relations and politics mainly revolves about the world how it is.

That’s why for future students this case study is best joined with an explanation of why European leaders were so eager to flatter Trump. The reality: Europe can’t defend itself without the United States, which in 2023 covered over 60% of NATO’s defence spending. Yes, as a superpower with bases around the globe, the US has greater obligations than Europe. But even Trump’s harshest critics can’t deny his point: European countries have underinvested in defence for decades.

So the political goal of European security and keeping the US on board, justified the means. As Belgium’s Defence Minister Theo Francken put it: “We flatter him because we can’t afford not to. Cutting our own defence to the bone for decades, comes at a flattery price.”

If European countries want to flatter Trump less in future, they’ll have to spend more on defence. The NATO summit was only the warm-up. Now come the long-term challenges for European defence:

Strengthening defence industry so Europe can actually spend the money.

Find the money for defence spending. Whatever route they choose, citizens will ultimately foot the bill.

Can Europe spend the money and strengthen its defence industry?

Focusing on budgets and percentages can make us forget that defence is about capabilities, not just spending. Money needs to turn into weapons, tanks and shells. Money doesn’t defend you, tanks do. Yet Europe’s defence industry struggles to ramp up production. Like we saw last year, when EU nations failed to deliver one million artillery shells to Ukraine within twelve months.

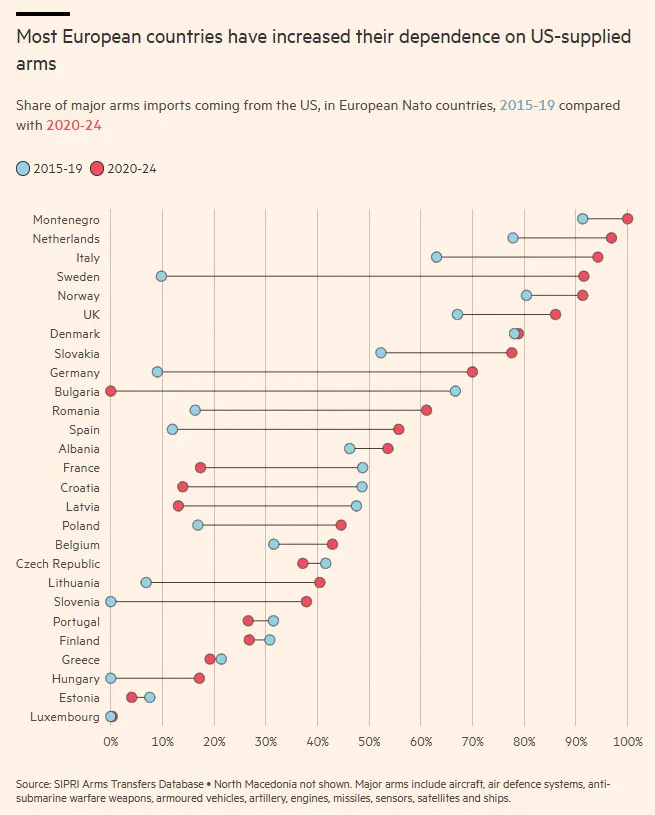

The first reason for this is chronic underinvestment in home-grown equipment and industry. While EU countries upped their defence budgets by 30% between 2021 and 2024 to €326 billion, only a small slice went to European equipment. Think-tank IRIS found that between February 2022 and June 2023, 78% of EU arms purchases were from outside the EU. Some 63% went to the US. As a result, Europe’s defence industry is far smaller than its spending suggests, leaving it reliant on US suppliers.

The second obstacle is fragmentation. Unlike the US or China, with giant defence firms benefiting from huge contracts, Europe’s defence sector is spread across many small players: Thales in France, Leonardo in Italy, Rheinmetall in Germany, plus over 2,500 SMEs. Every country backs its own defence champions, leading to inefficiencies, duplicated systems and higher prices. European firms produce 26 types of warship, 20 types of fighter jet and 15 tank models, whereas the US fields just one main battle tank. In 2021, only 18% of EU arms purchases were made jointly by two or more countries.

More importantly, fragmentation blocks economies of scale. Small players in small markets deliver small volumes. In 2024 Lockheed Martin, the world’s biggest arms maker, made more profit from weapons sales than the nine largest European firms combined. Meanwhile, Rheinmetall ended 2024 with a record €55 billion backlog of equipment still to be produced.

A third problem is European dependence on foreign microchips, critical raw materials and even steel. Supply-chain bottlenecks can choke production, like with China’s recent curb on rare-earth exports.

To boost output, the EU wants member states to pool more procurement. The aim is for 40% of purchases to be made jointly by 2030. The 150 billion European Defence Fund should invest in joint projects of EU countries and countries such as Canada and Norway, but explicitly leaves out the US. Europe must also invest jointly in seven critical systems, like missile defence and electronic warfare, for which it’s overly dependent on the US.

The endgame is a real European defence market and a stronger European industry. But national economic interests still back home-grown champions, leaving no European firm truly able to compete with their US and Chinese rivals on the global stage.

Who pays for the 5%?

NATO members have vowed to spend 5% of GDP on defence, with 3.5% on equipment and 1.5% on “societal resilience”, cyber defence and infrastructure. But that 1.5% carve-out risks letting countries label non-defence projects as defence spending. Italy, for example, wants to count €13 billion on Sicily’s Messina bridge as defence.

The real question is: how will that 5% be paid for? Higher defence spending means either more debt or cuts to other spending. In both cases, citizens will pay the price.

Borrowing and piling on debt is a short-term fix that lets politicians dodge the bill. The EU even encouraged extra borrowing by allowing defence spending up to 1.5% of GDP to be exempt from budget rules. But debt still rises. Larger debts mean higher interest payments down the road. After Germany announced €500 billion for defence and infrastructure, borrowing costs climbed across the eurozone. That extra spending squeezes future spending on health, education and innovation. The US now spends more servicing its debt each year than it does on defence. Europe doesn’t want to follow that path.

The other option, cutting spending elsewhere, requires difficult choices, like trimming social spending. Fewer pensions, more weapons. Mark Rutte has already called on governments to make “sacrifices,” meaning less on healthcare and welfare. He pointed out that Europeans spend up to a quarter of their national income on pensions, health and social security.

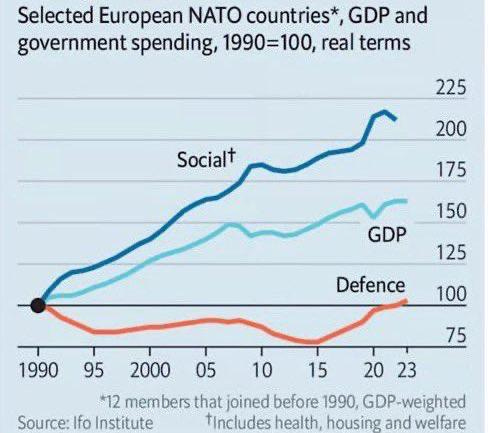

Indeed, social spending in Europe has risen far faster than GDP over the past 30 years, while defence budgets as a share of GDP have shrunk. A big chunk of that social outlay goes to pensions, 12.9% of EU GDP in 2021 versus just 1.3% on defence in 2022.

So Rutte may have a point. But slashing social benefits, especially pensions, to buy more tanks for a Russian threat many Europeans still see as ‘abstract’ is politically explosive. Think of the large-scale protests in France over raising the retirement age.

Yet pensions could also be part of the answer: euro-area pension funds held over €3.2 trillion in assets in 2023, and in countries like Sweden and the Netherlands they already invest in defence firms. But many EU pension funds steer clear of arms investments, citing ethical concerns and legal limits.

In any case, the NATO summit was just the warm-up. The real “fight” starts now: how will Europe turn political pledges into military power? Security comes at a price, and politicians must be honest about the bill. A 5% target that costs nobody anything is nothing more than a populist promise that undermines support for defence and NATO.